The Greatest Untold Mystery in

National Park Service History

In the depths of the Great Depression, Texas legislators viewed Big Bend as a nearly unlimited source of applications for New Deal appropriations and relief programs. Federal funds were available for construction of dams, highways, recreation areas, and even model communities—but only if a state could justify the need to fund these various public works projects.

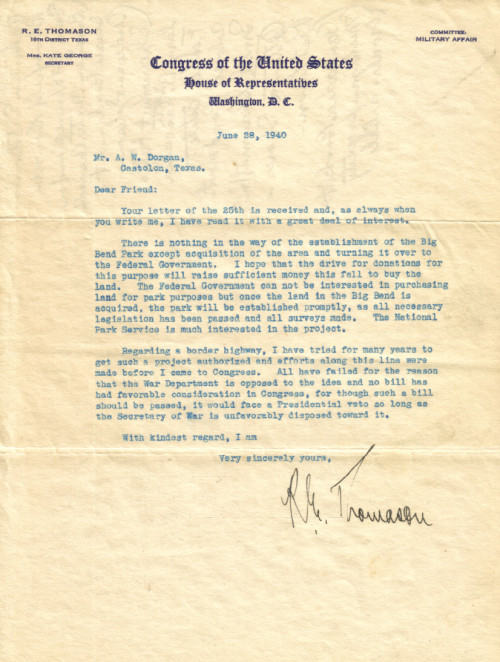

To build a New Deal international recreation area in Big Bend—complete with hydroelectric dams, multi-use water reservoirs, and a military border highway—Texas needed the support of key Congressional committees involving the War Department, Department of State, and Department of Agriculture. Fortunately for Texas, they controlled them all.

A state controlling key Congressional committees involved with the Departments of War, State, and Agriculture was unstoppable—given the right conditions.

Dams or Debt? The Battle for Big Bend

In 1935, Texans in Washington considered two package deals for developing hydroelectric dams, reservoirs, highways, and a recreation area in Big Bend. One option involved the Department of the Interior and their U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR). Under the Reclamation Act of 1902, states were required to repay construction costs to the federal government. The National Park Service opposed development beyond the bare minimum required to convert public lands into parks.

A second scenario involved the Department of State and their International Boundary Commission (IBC). Construction projects funded by the State Department did not require repayment or state contributions toward maintenance expenses. A border highway was possible with funding and assistance from the War Department and the Army Corps of Engineers. Development potential was unlimited.

National Park Service

vs.

Departments of War and State

In New Deal Big Bend, the National Park Service was simply outmatched.

The War Department approved projects affecting border security, but also projects affecting “public rights of navigation.” These projects included the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and Hoover Dam—or proposed dams and power lines crossing the Rio Grande. Influence with the Army Corps of Engineers and their construction projects involving flood control and hydroelectric power was essential. Yet unlike the TVA or Hoover Dam, a project in Big Bend involved Mexico–and the Department of State.

As a matter of ongoing foreign relations, all questions related to international park development fell under the purview of the Department of State. A key concern was that Mexican officials might use their cooperation in Big Bend as leverage in unrelated negotiations involving dams, power lines, and natural gas pipelines elsewhere along the Rio Grande. The State Department also controlled the International Boundary Commission, who oversaw construction projects along the Rio Grande and considered locations for future US-Mexican border crossings.

A Military Border Highway in Big Bend National Park

The idea of a military border highway paralleling the Rio Grande in Big Bend National Park is difficult for modern visitors to comprehend. Is it possible that the same Texans who proposed a national park in Big Bend also supported constructing a massive border highway useful for tourism, commerce, and troop deployment in the event of attacks by Mexican rebels?

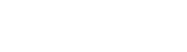

Rep. R. Ewing Thomason, of El Paso, wrote and introduced the enabling legislation for Big Bend National Park in March 1935. As Vice-Chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs, he also considered projects involving the War Department. Thomason worked closely with the National Park Service on the Big Bend park project for nearly a decade, but never shared his Congressional designs for a superhighway in Big Bend.

If Thomason and Texas wanted a border highway, why was it never constructed? After 75 years, this questions is answered by Thomason himself. A single unknown letter reveals the views of the War Department, President Roosevelt, and the Secretary of War regarding the border highway project that—per current accounts—never existed.

House Committee on Military Affairs

28 June 1940

R. Ewing Thomason, Vice-Chairman to A.W. Dorgan, Castolon (now Big Bend National Park)

We finally learn that the War Department opposed the Texas border highway project—not unusual considering the Department’s attitude toward any new military construction in the region. Thomason documents that Texas pursued the highway project “before I came to Congress” in March 1931 and that he personally “tried for many years.” He reports that “no bill has had favorable consideration in Congress” to create the highway.

If constructed, this highway would serve as the infrastructure for an international park and include a section of the Pan American Highway from Big Bend to El Paso.

Thomason also reveals the unknown opinions of President Roosevelt and the Secretary of War regarding a highway that does not exist. The Secretary of War was “unfavorably disposed toward it,” and if a bill for the border highway were passed by Congress, President Roosevelt would veto the legislation.

To see more unknown letters documenting the Big Bend conspiracy in Austin and Washington, click here.

R.E. Thomason, Vice Chairman

House Committee on Military Affairs

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Albert W. Dorgan

Department of State

Harry Hines Woodring

Secretary of War

New Deal Model Communities Along the Rio Grande

Cities of the Future

The idea of subdivisions and model communities emerged after World War One, as city planners searched for housing solutions that avoided problems associated with the crowded, congested neighborhoods of the Industrial Revolution. Landscape architects envisioned self-sufficient model communities with open spaces, affordable homes, and small plots reserved for subsistence agriculture. In 1922, Dorgan studied European architecture and visited the newly-established model community of Welwyn Gardens in Hertfordshire, England. Dorgan returned with a new vision for residential planning, and in 1926 he assisted with development of the Bloomfield Downs subdivision near Detroit, Michigan.

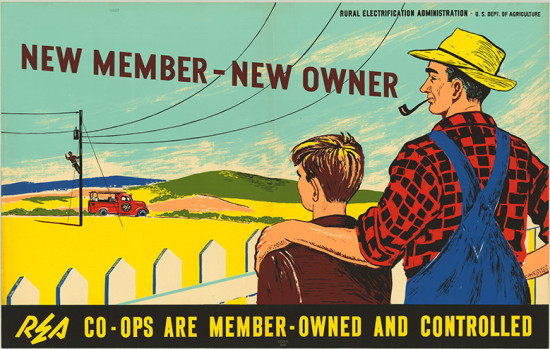

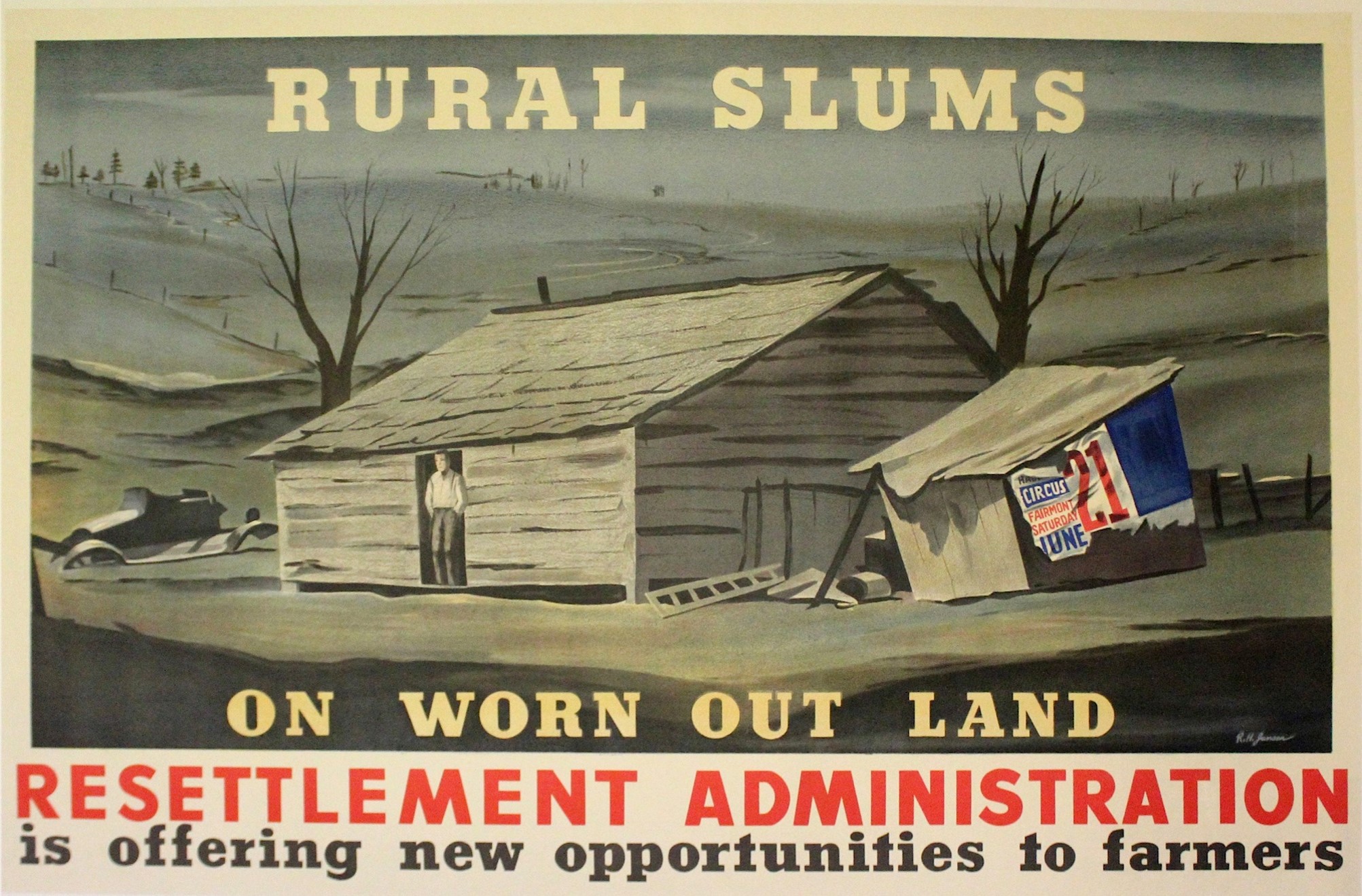

During the Great Depression, the need for model communities grew as many rural families abandoned their homesteads due to agricultural and economic distress. One New Deal solution involved creation of the Resettlement Administration and establishment of federal subsistence homestead colonies. In Texas, these projects included Dalworthington Gardens and Beauxart Gardens. These ‘garden cities’ offered families a means of survival through a combination of part-time employment and subsistence agriculture. Dorgan’s development plan for Big Bend included the creation of small irrigation districts perfect for subsistence agriculture, while the international park and public works offered employment opportunities for township residents.

Hydroelectric dams would generate power for communities from Big Bend to El Paso.

The Resettlement Administration helped create model communities and subsistence homestead programs.

The Birth of a City

A massive public works project involving dams, reservoirs and highways virtually guaranteed the creation of a large township in Big Bend. Labor camps grew alongside public works projects nationwide, as workers and private contractors established temporary residences. Public works agencies assisted in planning these model communities, in part to combat the public health and safety issues experienced by mining and railroad camps of the late nineteenth century. Orderly, well-planned communities reduced fire hazards, outbreaks of disease and vermin, and the dangers associated with shoddy construction, poor layout of utilities, and improper waste disposal.

Model townships often became New Deal tourist attractions themselves, showcasing the latest advances in American technology, housing, and the larger social vision of the New Deal itself. For Big Bend, a township within the international park—created by the dam, highway and park projects—was literally a tourist attraction within a tourist attraction. Visitors might explore both the park and model community, which provided housing for park staff and public works employees.