Big Bend International Park

The Big Bend International Park Saga Continues—Today!

The era of dams and artificial lakes in Big Bend ended with WWII and the establishment of Big Bend National Park in 1944, but the quest to establish a US-Mexican international park continued as both nations attempted to unite a shared ecosystem divided only by artificial political boundaries—and allow park visitors to move freely across the border.

Why a Big Bend Rio Bravo Binational Natural Area?

Preserving a Unique Landscape

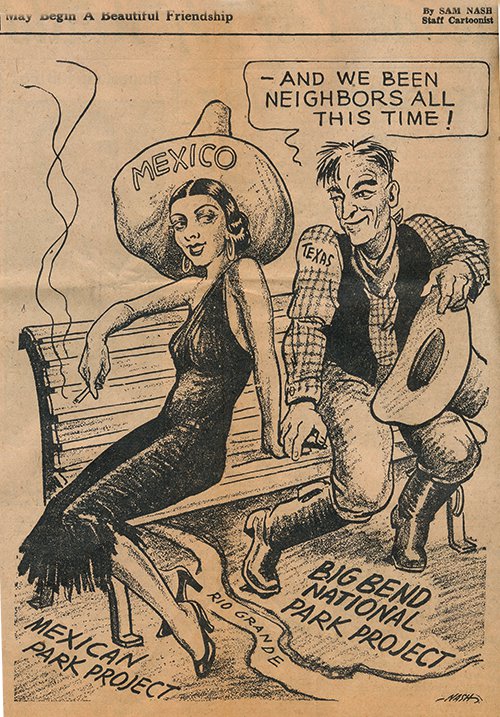

Most visitors fail to understand that the fate of lands on both sides of the US-Mexico border are linked. Destruction of either landscape destroys both. Leaving park lands vulnerable to unchecked development, road construction, gas pipelines, and light pollution, future generations will enjoy the unspoiled vistas of Big Bend only in photographs. Big Bend was one of the first ten “dark sky parks” in the world and protecting the night sky is a key preservation goal.

Cooperative Park Management

Park managers in Mexico and the U.S. already work jointly on many issues, but an international park designation would allow managers to work with their individual state and federal governments. Binational conservation increases cooperation involving search and rescue, control of exotic invasive plants, wildlife conservation, research, and restoration of natural fauna and flora. Cooperation also allows Mexico and the US to better address key issues including air quality, water management, and wildfire protection. Additionally, a unified park will increase the public use and enjoyment of publications, ranger-led activities, and border crossings. While both nations retain sovereignty over their respective parks and management policies, the mutual assistance encouraged by a single park is invaluable to current visitors and future generations.

Two Nations, One Park: Harmony on the Rio Grande

A joint US-Mexico park helps citizens of both nations to build stronger economic, social and conservation partnerships along the border. While issues including immigration, drug trafficking, and trespass livestock are ongoing problems, a strong partnership benefits all citizens—including those who have never visited the region. Along the 118 miles dividing Big Bend from the states of Chihuahua and Coahuila in Mexico, there is an opportunity for both nations to demonstrate to the world that conflict and conservation are not mutually exclusive.

The international park exemplifies the immense positive advancements that the US and Mexico governments can achieve via cooperation and collaboration. Aside from ecology and economics, establishing the park demonstrates that—even in times of political border conflict—both nations can pursue a great humanitarian project that permanently improves global perceptions of what a border can be.

Economic Advantages

The economic advantages of protecting this fragile desert mountain region and its wildlife cannot be overstated. A binational protected area is crucial to the quality of life for citizens of both nations who depend on ecotourism. Tourism is the lifeblood of many small communities along the Rio Grande, and a stable economy contributes to stable development. Simply put, the more valuable the tourism, the more valuable protection of the region becomes to both nations.

A thriving tourist industry based on sound conservation practices and limited development boosts the economy on both sides of the border via ecotourism. Conservation programs worldwide demonstrate that impoverished communities realize that ecotourism is more valuable than alternate means of short-term income, including mining, construction, and invasive regional development. Ecotourism is enduring and an infinite resource. Promoting the local economy has the added benefit of helping with the socioeconomic needs of many impoverished citizens already living within protected areas.

Frequently Asked Questions

If lands on both sides of the border in the US and Mexico are already protected, why is there a need for a binational natural area?

Any area designated as an international conservation effort enjoys added protection and effectively unites the various protected areas that are included in a proposed international park. While these areas remain under jurisdiction of their respective state and federal governments, a single park unit is the ultimate goal. Only a single, massive preserve will protect a scenic mountain landscape that encompasses lands of both nations. A united park is the only solution to preserving and managing this unique region in both ecological and aesthetic terms.This natural area would become a permanent monument and living symbol of peace between the U.S. and Mexico—regardless of border relations elsewhere along the Rio Grande. A binational protected area celebrates a united US-Mexico commitment toward conservation and provides an international meeting ground for citizens of all nations, who will not only enjoy the continued preservation of the landscape but also our shared border cultures.